Love is in the air and here it's even in the trees! So if champagne and chocolates have come your way, or you just fancy a cup of tea, snuggle up somewhere warm and enjoy a very unusual love story.

Dryad

In a quiet little

corner of the Botanical Gardens, between a stand of old trees and a

thick holly hedge, there is a small green metal bench. Almost invisible against

the greenery, few people use it, for it catches no sun and offers only a

partial view of the lawns. A plaque in the centre reads: In Memory of Josephine

Morgan Clarke, 1912-1989. I should know - I put it there - and yet I hardly

knew her, hardly noticed her, except for that one rainy spring day when our

paths crossed and we almost became friends.

I was twenty-five,

pregnant and on the brink of divorce. Five years earlier, life had seemed an

endless passage of open doors; now I could hear them clanging shut, one by one;

marriage; job; dreams. My one pleasure was the Botanical Gardens; its mossy

paths; its tangled walkways, its quiet avenues of oaks and lindens. It became

my refuge, and when David was at work (which was almost all the time) I walked

there, enjoying the scent of cut grass and the play of light through the tree

branches. It was surprisingly quiet; I noticed few other visitors, and was glad

of it. There was one exception, however; an elderly lady in a dark coat who

always sat on the same bench under the trees, sketching. In rainy weather, she

brought an umbrella: on sunny days, a hat. That was Josephine Clarke; and

twenty-five years later, with one daughter married and the other still at

school, I have never forgotten her, or the story she told me of her first and

only love.

It had been a bad

morning. David had left on a quarrel (again), drinking his coffee without a

word before leaving for the office in the rain. I was tired and lumpish in my

pregnancy clothes; the kitchen needed cleaning; there was nothing on TV and

everything in the world seemed to have gone yellow around the edges, like the

pages of a newspaper that has been read and re-read until there's nothing new

left inside. By midday I'd had enough; the rain had stopped, and I set off for

the Gardens; but I'd hardly gone in through the big wrought-iron gate when it

began again - great billowing sheets of it - so that I ran for the shelter of

the nearest tree, under which Mrs Clarke was already sitting.

We sat on the bench

side-by-side, she calmly busy with her sketchbook, I watching the tiresome rain

with the slight embarrassment that enforced proximity to a stranger often

brings. I could not help but glance at the sketchbook - furtively, like reading

someone else's newspaper on the Tube - and I saw that the page was covered with

studies of trees. One tree, in fact, as I looked more closely; our tree - a

beech - its young leaves shivering in the rain. She had drawn it in soft,

chalky green pencil, and her hand was sure and delicate, managing to convey the

texture of the bark as well as the strength of the tall, straight trunk and the

movement of the leaves. She caught me looking, and I apologised.

‘That's all right,

dear,’ said Mrs Clarke. ‘You take a look, if you'd like to.’ And she handed me

the book.

Politely, I took it. I

didn't really want to; I wanted to be alone; I wanted the rain to stop; I

didn't want a conversation with an old lady about her drawings. And yet they

were wonderful drawings - even I could see that, and I'm no expert - graceful,

textured, economical. She had devoted one page to leaves; one to bark; one to

the tender cleft where branch meets trunk and the grain of the bark coarsens

before smoothing out again as the limb performs its graceful arabesque into the

leaf canopy. There were winter branches; summer foliage; shoots and roots and

windshaken leaves. There must have been fifty pages of studies; all beautiful,

and all, I saw, of the same tree.

I looked up to find her

watching me. She had very bright eyes, bright and brown and curious; and there

was a curious smile on her small, vivid face as she took back her sketchbook

and said: ‘Piece of work, isn't he?’

It took me some moments

to understand that she was referring to the tree.

‘I've always had a soft

spot for the beeches,’ continued Mrs Clarke, ‘ever since I was a little girl.

Not all trees are so friendly; and some of them - the oaks and the cedars

especially – can be quite antagonistic to human beings. It's not really their

fault; after all, if you'd been persecuted for as long as they have, I imagine

you'd be entitled to feel some racial hostility, wouldn't you?’ And she smiled

at me, poor old dear, and I looked nervously at the rain and wondered whether I

should risk making a dash for the bus shelter. But she seemed quite harmless,

so I smiled back and nodded, hoping that was enough.

‘That's why I don't like

this kind of thing,’ said Mrs Clarke, indicating the bench on which we were

sitting. ‘This wooden bench under this living tree - all our history of

chopping and burning. My husband was a carpenter. He never did understand about

trees. To him, it was all about product - floorboards and furniture. They don't

feel, he used to say. I mean, how could anyone live with stupidity like that?’

She laughed and ran her

fingertips tenderly along the edge of her sketchbook. ‘Of course I was young;

in those days a girl left home; got married; had children; it was expected. If

you didn't, there was something wrong with you. And that's how I found myself

up the duff at twenty-two, married - to Stan Clarke, of all people - and living

in a two-up, two-down off the Station

Road and wondering; is this it? Is this all?’

That was when I should

have left. To hell with politeness; to hell with the rain. But she was telling

my story as well as her own, and I felt the echo down the lonely passages of my

heart. I nodded without knowing it, and her bright brown eyes flicked to mine

with sympathy and unexpected humour.

‘Well, we all find our

little comforts where we can,’ she said, shrugging. ‘Stan didn't know it, and

what you don't know doesn't hurt, right? But Stanley never had much of an imagination.

Besides, you'd never have thought it to look at me. I kept house; I worked

hard; I raised my boy - and nobody guessed about my fella next door, and the

hours we spent together.’

She looked at me again,

and her vivid face broke into a smile of a thousand wrinkles. ‘Oh yes, I had my

fella,’ she said. ‘And he was everything a man should be. Tall; silent;

certain; strong. Sexy - and how! Sometimes when he was naked I could hardly

bear to look at him, he was so beautiful. The only thing was - he wasn't a man

at all.’

Mrs Clarke sighed, and

ran her hands once more across the pages of her sketchbook. ‘By rights,’ she

went on, ‘he wasn't even a he. Trees have no gender - not in English, anyway

but they do have identity. Oaks are masculine, with their deep roots and

resentful natures. Birches are flighty and feminine; so are hawthorns and

cherry trees. But my fella was a beech, a copper beech; red-headed in autumn,

veering to the most astonishing shades of purple-green in spring. His skin was

pale and smooth; his limbs a dancer's; his body straight and slim and powerful.

Dull weather made him sombre, but in sunlight he shone like a Tiffany

lampshade, all harlequin bronze and sun-dappled rose, and if you stood

underneath his branches you could hear the ocean in the leaves. He stood at the

bottom of our little bit of garden, so that he was the last thing I saw when I

went to bed, and the first thing I saw when I got up in the morning; and on

some days I swear the only reason I got up at all was the knowledge that he'd

be there waiting for me, outlined and strutting against the peacock sky.

Year by year, I learned

his ways. Trees live slowly, and long. A year of mine was only a day to him;

and I taught myself to be patient, to converse over months rather than minutes,

years rather than days. I'd always been good at drawing - although Stan always

said it was a waste of time - and now I drew the beech (or The Beech, as he had

become to me) again and again, winter into summer and back again, with a

lover's devotion to detail. Gradually I became obsessed - with his form; his

intoxicating beauty; the long and complex language of leaf and shoot. In summer

he spoke to me with his branches; in winter I whispered my secrets to his

sleeping roots.

You know, trees are the

most restful and contemplative of living things. We ourselves were never meant

to live at this frantic speed; scurrying about in endless pursuit of the next

thing, and the next; running like laboratory rats down a series of mazes

towards the inevitable; snapping up our bitter treats as we go. The trees are

different. Among trees I find my breathing slows; I am conscious of my heart

beating; of the world around me moving in harmony; of oceans that I have never

seen; never will see. The Beech was never anxious, never in a rage, never too

busy to watch or listen. Others might be petty; deceitful; cruel, unfair - but

not The Beech.

The Beech was always

there, always himself. And as the years passed and I began to depend more and

more on the calm serenity his presence gave me, I became increasingly repelled

by the sweaty pink lab rats with their nasty ways, and I was drawn, slowly and

inevitably, to the trees.

Even so, it took me a

long time to understand the intensity of those feelings. In those days it was

hard enough to admit to loving a black man - or worse still, a woman - but this

aberration of mine - there wasn't even anything about it in the Bible, which

suggested to me that perhaps I was unique in my perversity, and that even

Deuteronomy had overlooked the possibility of non-mammalian, inter-species

romance.

And so for more than ten

years I pretended to myself that it wasn't love. But as time passed my

obsession grew; I spent most of my time outdoors, sketching; my boy Daniel took

his first steps in the shadow of The Beech; and on warm summer nights I would

creep outside, barefoot and in my nightdress, while upstairs Stan snored fit to

wake the dead, and I would put my arms around the hard, living body of my

beloved and hold him close beneath the cavorting stars.

It wasn't always easy,

keeping it secret. Stan wasn't what you'd call imaginative, but he was

suspicious, and he must have sensed some kind of deception. He had never really

liked my drawing, and now he seemed almost resentful of my little hobby, as if

he saw something in my studies of trees that made him uncomfortable. The years

had not improved Stan. He had been a shy young man in the days of our

courtship; not bright; and awkward in the manner of one who has always been

happiest working with his hands. Now he was sour - old before his time. It was

only in his workshop that he really came to life. He was an excellent

craftsman, and he was generous with his work, but my years alongside The Beech

had given me a different perspective on carpentry, and I accepted Stan's

offerings - fruitwood bowls, coffee-tables, little cabinets, all highly

polished and beautifully-made - with concealed impatience and growing distaste.

And now, worse still, he

was talking about moving house; of getting a nice little semi, he said, with a

garden, not just a big old tree and a patch of lawn. We could afford it;

there'd be space for Dan to play; and though I shook my head and refused to

discuss it, it was then that the first brochures began to appear around the

house, silently, like spring crocuses, promising en-suite bathrooms and

inglenook fireplaces and integral garages and gas fired central heating. I had

to admit, it sounded quite nice. But to leave The Beech was unthinkable. I had

become dependent on him. I knew him; and I had come to believe that he knew me,

needed and cared for me in a way as yet unknown among his proud and ancient

kind.

Perhaps it was my

anxiety that gave me away. Perhaps I under-estimated Stan, who had always been

so practical, and who always snored so loudly as I crept out into the garden.

All I know is that one night when I returned, exhilarated by the dark and the

stars and the wind in the branches, my hair wild and my feet scuffed with green

moss, he was waiting.

‘You've got a fella,

haven't you?’

I made no attempt to

deny it; in fact, it was almost a relief to admit it to myself. To those of our

generation, divorce was a shameful thing; an admission of failure. There would

be a court case; Stanley would fight; Daniel

would be dragged into the mess and all our friends would take Stanley's side and speculate vainly on the

identity of my mysterious lover. And yet I faced it; accepted it; and in my

heart a bird was singing so hard that it was all I could do not to burst out

laughing.

‘You have, haven't you?’

Stan's face looked like a rotten apple; his eyes shone through with pinhead

intensity. ‘Who is it?’

What was I to say? He'd

probably think I’d gone crazy.

‘I'll bloody well make

you tell me,’ he snarled. I smelt his sour breath as he wrenched my arm behind

my back, but the thought of The Beech's calm strength gave me courage. I heard

Daniel calling uncertainly from the top of the stairs. The noise had woken him.

‘Let me go to him,’ I

begged. Stan hesitated.

‘Please.’

He released me and

turned away. I hurried upstairs, my arm throbbing as the blood rushed back.

When I came down again,

Stan was sitting on the sofa, his face hidden in his hands. The bottom stair creaked

and he looked up at me. ‘If you want to keep the lad, you'll have to give your fella

up,’ he said flatly. ‘We'll move away.’

‘No!’ the word escaped

me like a cry of pain.

Stan looked deflated. I

thought of a picture I had once seen of Rodin's Burghers of Calais:

strong men bowed down helplessly under the weight of their manacles. I felt a

twinge of pity for Stan, but I couldn't help but compare him unfavourably with

my magnificent lover.

At last he said, ‘We'll

talk about this in the morning.’ He disappeared into our bedroom and came out

with an armful of blankets. ‘I'll sleep out here.’

I lay awake for hours in

our cold bed, tom between anxiety and elation; my fingers twisted the blue

candlewick bedspread. I knew I ought to feel guilty, but I heard the whisper of

leaves against my cheek and felt The Beech's smooth trunk clasped in my arms.

Stan and I didn't talk

the next morning, or the one after that; he was morose and withdrawn. Often, I

caught him watching me like a hungry dog at the butcher's door, but he left me

alone. My serenity seemed to baffle him.

We agreed to stay

together for Daniel's sake. After a while, Stan started to go out most evenings

after supper. I never asked where he went, but the way Brenda Whitely, who ran

the Post Office, avoided my eyes when I went in to buy something, and the

pitying glances of our friends and neighbours told their own story. When he

died I didn't marry again; I already had everything I wanted.’

The rain had stopped and

the pale blue sky looked newly varnished. I felt stiff and hungry. ‘I'm so

sorry’ said Mrs Clarke, noticing my discomfort. ‘I shouldn't be keeping you

here talking like this.’ She looked at me quizzically, but I just murmured a

polite nothing. I didn't want to discuss my problems with a stranger, even a

kind one. Yet afterwards, I thought a great deal about her strange story. There

was something inspirational about it; she had showed me that happiness can be

found in unexpected places.

Years later, happily

married for a second time and a successful freelance journalist, I had almost

forgotten Josephine Clarke, until one wet Sunday afternoon, glancing through

the papers, I noticed a photograph of an elderly lady who looked familiar. The

article was about an exhibition of her work at a Bristol gallery. The writer described her

drawings as exquisite and sensuous; food for the soul; an oasis of calm in a

frantic world. There were a couple of illustrations of her studies of trees;

they had the delicate strength of Leonardo Da Vinci's drawings of nature. The

artist's name was Josephine Clarke. I planned to visit the exhibition but I had

a deadline for a magazine feature and never made it.

On the evening of 15th October 1987, hot winds moving

up from Africa collided with the glacial air of the Arctic

and soared above it, creating a drop in pressure. By six o'clock, the pressure

gradient had risen steeply. Perhaps, said the Met Office, a strong jet stream,

caused by a hurricane moving up the east coast of the USA and across the Atlantic, had reacted with

exceptional warming over the Bay of Biscay.

Vapour condensed into clouds and released enormous energy which drove the storm

winds towards Britain.

At first it seemed as if

the storm would track along the English Channel but instead, in a famous low

point in the career of Michael Fish, it turned north and swept through southern

England,

leaving devastation in its wake. By morning, fifteen million trees lay

uprooted.

Three years passed and

the trees, but not their memory were gone, when I noticed the Bristol gallery was mounting another

exhibition of Mrs Clarke's work. The article said she had died in 1989.

This time, I was

determined not to miss the opportunity, but when I walked into the gallery, the

drawings were not at all what I had expected. There was none of the peace and

serenity I recalled, only turmoil and despair. I moved along the walls,

surprised by what I saw; each picture was a poignant cry of sorrow and despair.

Then I read the information leaflet the girl in charge of the gallery had

pressed into my hand at the door; these drawings had been done between 1987 and

1989. Of course! The October storm: it would have been cataclysmic for

Josephine Clarke.

I walked slowly back

along the line. One drawing in particular exuded so much raw emotion it was

painful to behold; it showed a beautiful copper beech tom from the earth, its

sinewy roots snapped like matchsticks. The grain of the bark had been

meticulously delineated; where the trunk had split at the bole, I could almost

imagine that the markings were shaped like a heart.

In the last room was a

graceful figure, about eighteen inches high. It was carved of polished,

honey-coloured wood. The figure was a woman, in flight from an unseen pursuer;

as I looked more closely, I saw her torso was fashioned as if it were partially

covered in thin bark. At the ends of her streaming hair, tiny leaves formed;

thick, fleshy tree roots embraced her nimble feet.

The caption read Daphne fleeing Apollo. The girl in

charge of the gallery came over smiling. ‘Quite a relief after those earlier

drawings isn't it?’ she said. ‘Apparently she suffered a nervous breakdown in

late 1987 and never really recovered. She carved this at the very end of her

life. Very beautiful don't you think? As far as we know, it's her only work in

wood. It's made of beech.’

When I got home, I

looked up the story. It told how the god Apollo saw the nymph Daphne and instantly

fell in love with her, but she, preferring to roam the woods than be in the

company of gods and men, fled from him. He had almost caught her when she

reached the banks of the river Peneus, her father. Terrified, she begged her

father for help. As Apollo was just about to seize her, Peneus transformed her

into a tree.

I went back to the

gallery before the exhibition ended and bought the figure; it still sits on my

desk to remind me of Mrs Clarke. She probably never knew how much she helped me

that day.

When I applied for

permission to put the bench with the plaque in the Botanical Gardens, the

Keeper was very helpful; I could choose the place; the only proviso was that

the bench must be made of wood or metal. On a cool, autumn afternoon, I walked

around the paths and lawns for hours until I found the right spot; a quiet

corner, hidden among Mrs Clarke's beloved trees. The bench I ordered was made

of metal, as she would have wanted.

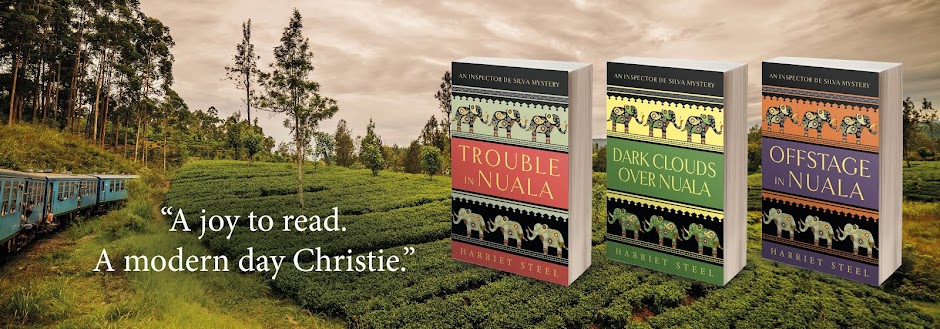

Dryad comes from Harriet Steel's collection of short stories, Dancing and Other Stories available on Kindle at viewBook.at/danc_ing and sold in aid of WaterAid.